Roon, algorithmic choice and platform middleware

My search for a better way to stream music led me to a service called Roon last week. Roon is great, but rather than write about that, I want to write about what Roon can tell us about algorithmic choice and the notion of platform middleware.1

Let’s start with the idea of abundance. As Albert Wegner puts in The World After Capital:

Digital information is already on a clear path to abundance: we can make copies of it and distribute them at zero marginal cost, thus meeting the information needs of everyone connected to the Internet.

This abundance has created a new economic challenge. Rather than the challenge of how we distribute scarce resources to a large group of people, we now have to decide which resources people should consume given a (near) infinite supply, and, in some cases a relatively limited amount of time to consume it. Some of these decisions are somewhat banal, for example, which movie or TV show I should watch next? But not all are like this. Which hairdryer should I buy might seem trivial, but when an algorithm decides which product is ranked first (and thus more likely to be bought) we are giving it an extraordinary amount of power. Similarly, when we allow an algorithm to decide which news article comes first, or which person’s voice is heard the loudest.

It’s tempting to view algorithms as an exogenous force. Something independent of human biases and thus well placed to make important decisions such as the ones described. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth. Algorithms are socio-technical systems that, even with the best intentions, are imbued with all the biases inherent to humankind. They can be presented as independent while in reality promoting the agenda of their creator.

Centralised control over algorithms with power of this kind is something that society must reject. But that still leaves us with a new challenge of the second industrial revolution: in a world of abundance, how do we decide what people consume?

The state, peer recommendation, organisations, human editors and many other modes of discovery will play their role (as they always have), but algorithms powered by data are part of our future too. If we agree that algorithms represent new forms of power, and aren’t comfortable with the centralisation of that power, something needs to change.

Algorithmic choice is one idea that requires closer examination. If we are able to choose the algorithm that sorts, filters and flags content on our behalf the inherent power of algorithms becomes more diffuse. Algorithmic choice within e-commerce may allow someone to preference specific brands, products that were made locally or ones that meet certain environmental criteria. Similarly, within social media it could allow for a plurality of moderation services or attempt to make ones feed more representative of public opinion and less of a filter bubble.

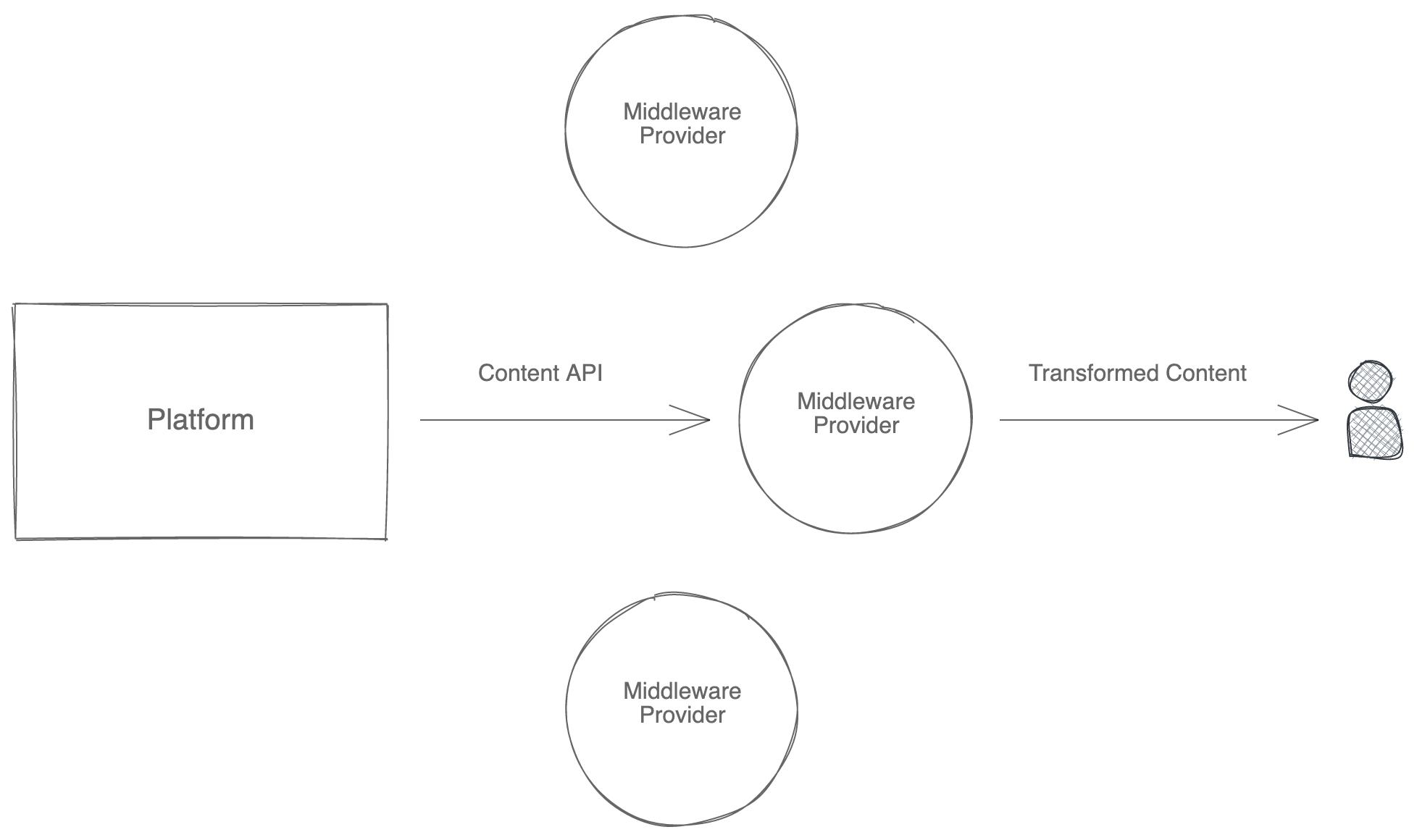

Fortunately, these ideas are beginning to gain traction. Jack Dorsey, the CEO of Twitter, has voiced support for a “marketplace” of algorithms, and at the end of last year Francis Fukuyama released a report that called for the creation and enforcement of algorithmic middleware providers.

This brings me to Roon. First, consider how music streaming platforms like Spotify and Tidal choose to tackle the problem of abundance that we have just highlighted. From their growing libraries of 70M+ songs they present us with ideas of what to listen to next. If you’re like me, you find this grating, as you want to browse the music yourself, but if you like the recommendations you’re limited to the platform’s technology. And, as we already know, those recommendations come with the biases / economic goals of their creators. Now consider how Roon operates. After creating my account, Roon asks me to connect it to my streaming provider (Tidal or Quboz only I’m afraid). Roon then imports my entire collection and begins to re-organise the music based on their discovery interface. Similarly, it introduces a whole new set of algorithms to surface music based on my existing collection and based on things it thinks I’ll like.

The critical difference however is their economic incentive. Roon’s model isn’t based on micropayments dished out to the holders of music copyright. You can rent it off them for £12.99 a month, or your can purchase a lifetime license for £600.

As an aside, I really like the trend towards offering lifetime access for a single price, but I’ll save that for another post.

Roon is beholden to me, their only customer. Their goal should be to make my listening experience as enjoyable as possible. Tidal, Spotify et al. might argue that this is their goal too, but the truth is that as a multi-sided platform (or aggregator as Ben Thompson likes to call them) their motivation is not entirely aligned with mine.

It’s worth noting that the Room model creates a significant degree of disintermediation, or, in non-technical terms, I no longer use the Tidal apps to listen to music. Tidal may not be best pleased about this, but at the same time they are still receiving the £29.99 a month I pay them for access to the music library, so the impact on their business is not universally bad. Social media companies may be less comfortable with this outcome however as they are “free” to consume but monetised via ads. If I no longer access their front end, their revenues quickly drop to zero. This isn’t a blocker for the middleware model however, it just requires the platform to integrate a choice of algorithmic middleware themselves.

For those interested in algorithmic choice and the middleware model, Roon, and its relationship with Tidal / Quboz, is worthy of closer examination than a Friday morning blog post can afford. For my money, Roon is one of the best examples of commercially successful platform middleware available today. And only exists due to a quirk of history that has created multiple layers of rights over how digital music is consumed.

It’s probably obvious from my tone that I think algorithmic choice has the potential to untangle many of the messy issues the last 20 years of platform development has left us with. It is not a panacea however, we’ll need many new tools to fix the world we have today and however good I think this one is, it remains just one.

1 If you're interest to learn more about Roon I'd recommend reading this overview from What HiFi as it's not a service that can be explained that easily.